EV Charger Accessibility

A report from our on ground survey

This is a guest post by Jaideep Saraswat, associate director at Vasudha Foundation. Jaideep works at the intersection of clean energy, electric mobility and artificial intelligence. He has contributed to various work streams involving EV charging infrastructure, battery refurbishment, and zero emission trucks always aiming to support more sustainable and efficient transportation systems. He’s interested in how technology can enable practical climate solutions.

Views mentioned here are personal and do not represent his organisation.

While the expansion of Public Charging Stations (PCS) is critical for vehicle electrification, it must also be accessible. According to government census data of 2011, India is home to 26.8 million people with disabilities. Over the past decade, approximately 156,000 adapted vehicles have been registered for use by drivers with disabilities. Ensuring that these individuals can independently access EV charging infrastructure is not only a matter of policy alignment, but a question of equity and mobility justice.

Today, we report on an on-ground survey of public EV charging infrastructure across multiple cities in India has been completed, covering installations by various public and private charge point operators using diverse charging hardware.

The summarised google sheet of our findings is available for premium subscribers only. Please drop me a message and I’ll share the link with you.

Before we dive into today’s report, here are a few things.

We would like to thank our premium subscribers for enabling this story. Become a paid subscriber to ExpWithEVs today and help us do more on ground stories and maintain our independent voice.

If you are interested to pitch a story to us, then please fill this form.

Last week, we wrote about Office of the PSA to the Prime Minister’s report on zero emission corridors. We took a hard look at the public and private charging infrastructure along these routes.

We are hosting an interactive AMA (Ask Me Anything) session on charging infrastructure on 18th June 2025.

The Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (DEPwD), Government of India, launched the “Accessible India Campaign” (Sugamya Bharat Abhiyan) in 2015 as a flagship initiative aimed at promoting accessibility for persons with disabilities. The campaign focuses on developing universally accessible infrastructure across four key areas: the built environment, transportation systems, information and communication technology, and the integration of Indian Sign Language.

Accessibility, in context of public charging infrastructure, must extend across a broad spectrum of users, including wheelchair users and individuals who rely on mobility aids, those with limited upper-body strength or dexterity, people of short stature, and older adults experiencing age-related mobility limitations. It should also consider individuals with visual or cognitive impairments, as well as users who face hearing difficulties or language barriers.

Recent international research and user feedback indicate a growing willingness among persons with disabilities to transition to EVs, provided the infrastructure is designed to accommodate their needs. However, it is important to note that such research has primarily been conducted in non-Indian contexts, and no comprehensive, India-specific study or user feedback survey currently exists to validate this trend domestically. As India now lays the foundation for a large-scale rollout of PCS, it presents an exciting and timely opportunity to embed accessibility into the infrastructure from the outset. Doing so will ensure the system is inclusive by design and help avoid costly, inadequate retrofits in the future.

Key Frameworks

Global - PAS 1899 and International Best Practices

One of the most comprehensive efforts to standardize accessible charging infrastructure comes from the UK with the release of Publicly Accessible Specification (PAS) 1899 in October 2022.

Developed in collaboration with disability advocacy groups, EV manufacturers, and infrastructure providers, PAS 1899 sets out minimum technical specifications for accessible PCS. It addresses charger placement and spacing, including reach and maneuverability for wheelchair users; clear ground space and unobstructed pathways; interface usability in terms of height, tilt, and more; cable management systems to minimize trip hazards and physical strain; and real-time information access, including visual cues and multilingual support.

Indian

India has already laid a strong foundational framework for accessibility through the Central Public Works Department (CPWD) Manual on Barrier-Free Built Environment (2016), which is aligned with the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016. Key provisions that can be adapted to public charging infrastructure include:

Approach and Site Design (Chapter 4):

Minimum 1.5 m wide clear paths to enable unhindered wheelchair access.

Tactile warning surfaces near obstacles and curbs.

Non-slip flooring, level differences minimized to under 10 mm or mitigated with ramps.

Access routes free from obstructions with turning radius for wheelchairs (1.5 m min).

Handrails and Grab Bars (Chapter 9):

Installation of grab bars where manual support is required for standing or transferring.

Handrail diameters between 32–40 mm and positioned between 760 mm–900 mm height, with non-slip grip and extended ends for safety.

By synthesizing these global and national guidelines, India can chart a path toward standardized, accessible public charging infrastructure that is not only compliant but transformative, empowering millions of users who have historically been excluded from mainstream mobility systems.

Methodology

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the real-world accessibility of PCS for persons with disabilities in India, an on-ground survey was conducted across multiple urban settings. The cities/regions selected for the study were National Capital Region (NCR), Bhopal, and Ayodhya. They were chosen to represent a spectrum of urban contexts, covering metropolitan (Tier 1), mid-sized (Tier 2), and emerging urban areas (Tier 3), respectively. This stratified selection was intended to capture diverse infrastructural realities and implementation levels of accessibility standards across different tiers of urban development.

In total, 20 PCS were surveyed: approximately 10 in NCR, 6 in Bhopal, and 4 in Ayodhya. The sample size aimed to balance breadth with practical feasibility, while still offering meaningful insights into regional trends.

Key Evaluation Parameters

The assessment framework was built upon accessibility benchmarks outlined in PAS 1899 and India’s CPWD Manual on Accessible Built Environment. Based on these guidelines, each charging station was evaluated using a detailed checklist of physical and interface-related parameters, including:

Charging Gun Design: Height from ground level and presence of a rotating handle to enable easier reach and manoeuvrability.

Human-Machine Interface (HMI) Screen: Presence of HMI screen and right placement from the ground, with a slight upward tilt for improved visibility and reachability.

Dedicated Parking: Availability of designated parking spaces for persons with disabilities.

Cable Management System: Presence of retractable or manageable cables that can be easily handled without requiring excessive strength or dexterity.

Ergonomic Gripping Area: Charging guns featuring grip diameters between 19–43 mm to accommodate users with limited hand mobility.

Interface Language Options: Ability to switch languages on the HMI for non-native speakers.

Easy-Read Operating Instructions: Simple, graphic-supported steps for users with cognitive or learning disabilities.

Screen Visibility: Adequate daylight readability, either through high-contrast adaptive screens or physical canopies to minimize glare.

Support Access: Display of a 24x7 helpline number for user assistance.

Clear Access Space: At least 1.2 meters of clear space in front of the charging unit to enable unobstructed wheelchair access.

Preview via App: Charging apps offering real photographs of the stations to help users pre-assess suitability based on their specific accessibility needs.

While these parameters provide a robust baseline for evaluating accessibility, it is important to note that they are not exhaustive. They were selected to serve as a representative yet practical set of criteria for assessing inclusivity at PCS and can be expanded upon in future studies as awareness and standards evolve.

Survey findings

The survey results reveal a significant gap between current on-ground PCS and the standards needed to ensure equitable access for people with disabilities. While some isolated improvements were noted, accessibility has largely not been incorporated as a foundational design principle.

1. Charging Gun Height

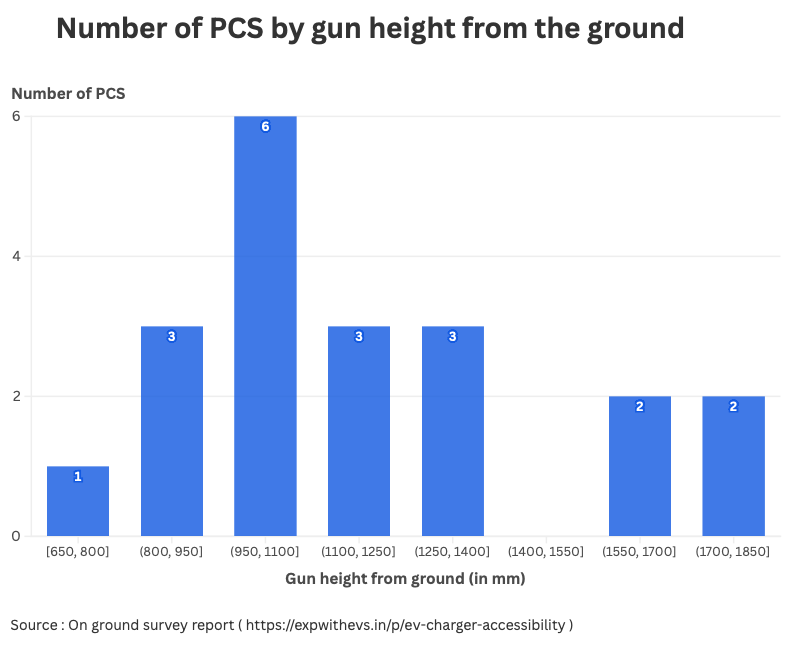

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of charging gun heights across the surveyed PCS. A clear concentration is observed in the 950–1100 mm range, with 6 out of 20 stations falling into this category. This exceeds the recommended range of 800 mm to 950 mm set by PAS 1899. Additionally, a significant number of stations fall into even higher height brackets, underscoring the potential accessibility challenges for persons with disabilities.

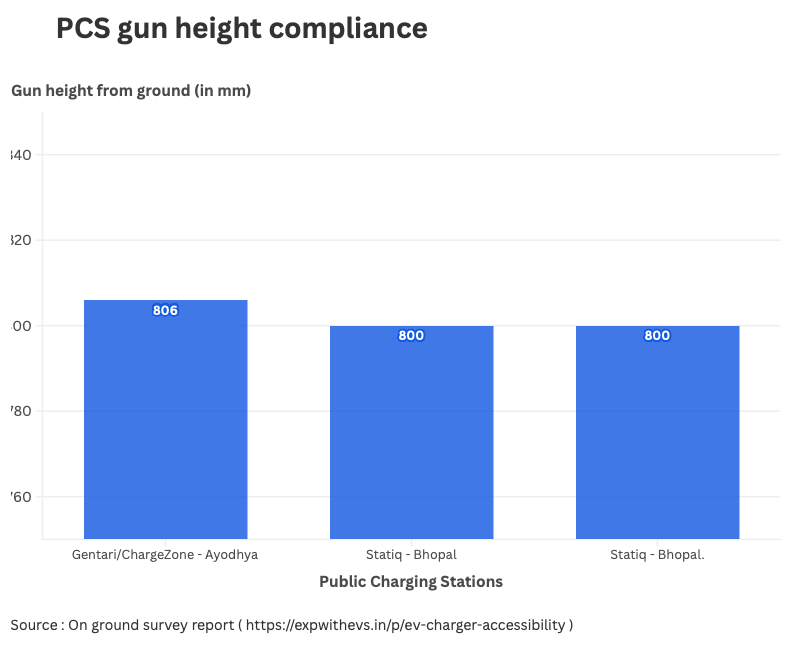

The average height of charging guns across the surveyed stations was approximately 1174 mm from ground level. Only three charging stations across all three cities met this height criterion, as shown in Figure 2. The deviation in height poses a significant usability challenge for individuals using wheelchairs or those with short stature/limited reach.

2. Rotating Charging Gun Handle

None of the surveyed stations incorporated rotating handles on charging guns, a design feature that helps users better align the connector with the vehicle inlet while minimizing physical effort and cable torque. The absence of this feature reflects a missed opportunity to ease physical handling, particularly for those with limited strength or dexterity.

3. Human Machine Interface (HMI) Screen Placement and Tilt

Only two stations in NCR, both operated by ATGL (Figure 4), had an HMI screen tilted between 10 to 20 degrees, as recommended. However, these HMIs still failed to meet the correct height range. The bottom edge needed to be at least 800 mm and the top no more than 1300 mm (as per PAS 1899). Misalignment in HMI height continues to be a barrier for wheelchair users or individuals with height-related reach limitations.

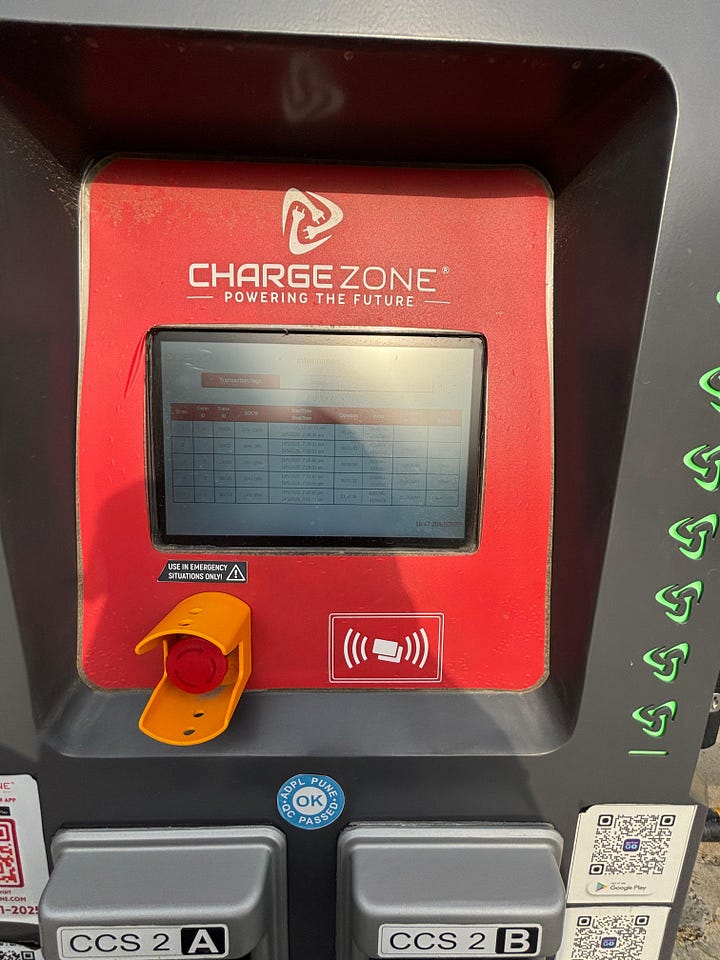

That said, the presence of an HMI screen itself is a critical feature, and encouragingly, all surveyed DC PCS were equipped with HMIs. The HMI serves as a crucial communication tool that significantly enhances the overall user experience. It provides real-time feedback and transparency, for instance, explaining why a vehicle may not be charging at full capacity despite the charger's rated output. It also aids in diagnosing issues by displaying clear error messages or reasons for failed charging sessions, helping to avoid user confusion or frustration. Moreover, HMIs offer live updates on charging progress, estimated time remaining, and total energy delivered. This information is vital for all users, and especially helpful for those who may face difficulties interacting with mobile apps or require straightforward, visual feedback during the charging process.

4. Dedicated Accessible Parking

Across all surveyed locations, no charging station provided dedicated parking bays for persons with disabilities. While this can be partly attributed to the current industry focus on maximizing station utilization and Return on Investment (ROI), it highlights the critical need to plan for inclusive infrastructure as station density grows. Encouragingly, ChargeZone station in Ayodhya demonstrated compliance with the recommended 900 mm (as per PAS 1899) separation between parking bays, facilitating easier wheelchair manoeuvring (Figure 5).

5. Cable Management Systems

Only Jio-bp’s station in Bhopal featured a cable management system (Figure 6), which supports the unused length of the cable and minimizes physical strain during use. In most other stations, trailing cables were seen cluttering the area (Figure 7), creating tripping hazards and restricting movement, which is problematic for users with mobility aids or vision impairments.

6. Charging Gun Grip Ergonomics

A positive outcome was noted regarding the design of charging gun grips. All surveyed stations featured handles with grip diameters between 19 mm to 43 mm (as per PAS 1899). This range accommodates users with different physical abilities, including those who may require two-handed operation or have reduced grip function due to amputation or aging.

7. Language Accessibility in HMI

No charging station offered the option to change the language of the HMI interface. For non-native speakers or those not fluent in the default language, this lack of linguistic flexibility can create a major barrier to independently operating the station. Enhancing HMI systems with multiple language options is a key step toward universal accessibility and should be prioritized in future deployments.

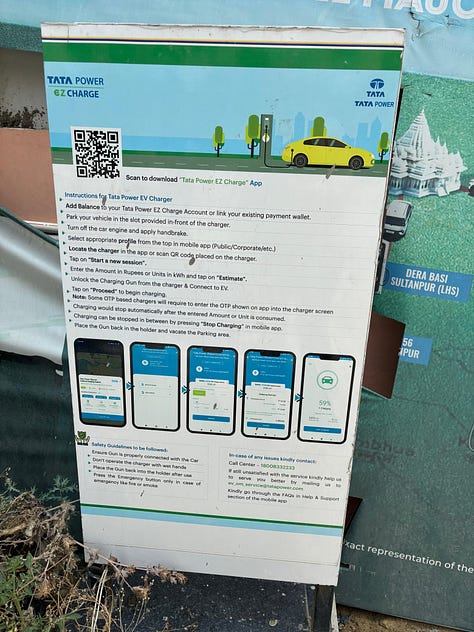

8. Easy-to-Understand Operating Instructions

Nearly all charging stations featured “easy read” step-by-step instructions supported by visual graphics (Figure 9). This approach is especially helpful for users with learning or cognitive disabilities and represents an encouraging trend toward more inclusive user interfaces.

9. Support and Helpdesk Information

All surveyed stations prominently displayed a 24x7 helpline number, offering a vital support option for users encountering difficulties. This is a commendable practice that should continue as a standard industry norm.

10. HMI Visibility in Daylight

Most stations still lacked design elements like anti-glare screens or overhead canopies to ensure clear visibility of the HMI interface under bright daylight conditions. A few exceptions, as shown in Figure 10, incorporated canopies, which significantly improve usability for users with visual impairments.

11. Accessible Pathway Width

Only one station in Noida and two stations in Ayodhya offered a minimum clear access width of 1.2 meters (as per PAS 1899) in front of the charging unit, essential for wheelchair users to approach and operate the charger comfortably (Figure 11). This shortfall is a direct impediment to independent use for mobility-impaired users.

12. App-Based Station Previews

Finally, none of the charging apps linked to the surveyed stations provided real, on-site photographs to help users assess station suitability in advance. Such visual previews can be especially valuable for people with disabilities to make informed decisions about whether a station meets their specific accessibility needs.

Conclusion

The findings from this survey, though based on a relatively small sample of 20 PCS across three cities, provide valuable directional insights into the current status of accessibility in EV infrastructure. While isolated examples of good practice were observed, such as ergonomic charging gun grips, “easy read” instructions, and the consistent display of helpline numbers, the broader landscape of PCS in India reveals a fragmented and inconsistent integration of accessibility features. Critical aspects such as appropriate HMI placement and tilt, clear manoeuvring space, dedicated parking bays, cable management, and language options remain largely overlooked. This highlights an urgent need to move towards a systemic, inclusive approach in the design and deployment of PCS.

As India accelerates toward its electric mobility targets, accessibility must be treated as a foundational design principle. The creation of India-specific accessibility standards for PCS is a crucial next step. These standards must be aligned with ground realities and informed by international best practices. Moreover, mandatory adherence to these standards should be enforced.

Equally important is the active inclusion of disabled users in the policy, design, and feedback loops of PCS development. Establishing a mechanism to collect, monitor, and respond to real-time user feedback can ensure that evolving needs are continuously addressed, and accessibility remains dynamic and user-informed rather than static and checklist-driven.

Embedding accessibility through policy, regulation, and inclusive design will not only uphold the rights of persons with disabilities but also build greater public trust, foster wider adoption, and create a truly equitable transition to electric mobility.

This piece is proprietary and a property of ExpWithEVs. You may not republish, copy, edit, repost or reshare this piece without prior written confirmation from ExpWithEVs via email : priyans@expwithevs.in